A Guide to Writing Effective Research Reports

Don't let your reports die in a dusty Google Drive folder

👋🏻Hi, this is Nikki with a 🔒subscriber-only 🔒 article from User Research Academy. In every article, I cover in-depth topics on how to conduct user research, grow in your career, and fall in love with the craft of user research again.

I’ll say it:

Writing research reports can suck. Big time.

There are difficult things in user research that I’ve been able to get behind and actually start to enjoy like whiteboard challenges or stakeholder management. I even eventually got over my fear of writing case studies.

But, holy moly, there is something about writing a research report that still gets me. Like, even today with my consultancy clients, over ten years into this wonderful craft, I still get nervous writing research reports.

Why?

They are so important!

They are the story behind the data, giving people the information they asked for to make less risky decisions. They are the epitome of our research.

Maybe that sounds dramatic, but I honestly feel like effective reports can make or break how user research is viewed at an organization.

However, I didn’t always “believe” in research reports, just like for a while I didn’t “believe” in using quantitative data or surveys, or didn’t “believe” in personas — you might spot a trend: I didn’t believe in things I was scared of.

I tried to avoid writing reports by doing other things like demo desks, movie nights, and session snapshots (all of which I’ll talk about later). While there is nothing wrong with these methods of sharing research, there is still a time and a place for reports.

So, while I am still nervous about them, over the years, I’ve honed some effective report-writing skills and techniques, which, if you are on the same side of the report-writing fence, then hopefully they will help.

Let’s dive in.

What Goes Wrong with Research Reports

When I finally decided to tackle writing research reports and getting more comfortable with them, I knew I had to investigate all the things going wrong with my research reports. This struck true fear in me. I was all for constructive critcism, but I was also scared of it — what if I asked what was wrong and enough people recognized me as the impostor I felt I was?

It was less about receiving criticism and more about opening Pandora’s box to find out what was wrong, only for everyone to realize I had no idea what I was doing. There wasn’t a worse user research nightmare for me.

But, as I have found out again and again in my career, the best way to figure out what to do better is to uncover what’s going wrong. And there was no one better to do that with than my product managers, as they were (and are!) the users of my research reports — they would know best what was happening.

Although I often interview my stakeholders broadly when I join a company, and also send out stakeholder satisfaction surveys after most of my projects, this was a different kind of initiative. I wanted to pinpoint exactly what was going wrong with my reports, and I wanted to also reach out to previous stakeholders as well as product managers I knew but hadn’t directly worked with.

Basically, I wanted to run a research study on what’s wrong with research reports, both from a more personal level of what’s wrong with mine, and then, more generally, what stakeholders find painful about research reports. I decided this was likely the best way forward as it gave me a certain objectivity when it came to this topic — I was simply a researcher researching.

The Study

I recruited various stakeholders, focusing in on product/tech teams, such as designers, product managers, and developers, who had engaged with user research reports at least twice in the past three months. I decided on 1x1 interviews with a follow-up survey to help me understand the insights more broadly.

I ended up interviewing about twenty five stakeholders. Most of them ended up being product managers, with a few designers and developers. The feedback felt consistent across the various roles, with a few exceptions, so I decided at that point, not to do a phase two and three of research just looking into designers and developers.

My questions consisted of things like:

Walk me through the last time you engaged with a user research report, what was that experience like?

Describe the number one problem you had with the report.

Explain how you used the report, including the most useful information.

Talk me through the parts of the report less helpful, and why?

Tell me about a research report that was hugely successful. Why was it successful?

Describe a research report that you had a hard time with and why?

Tell me about the number one thing missing from research reports.

Each interview was about 60-90 minutes and stakeholders showed me direct examples (of my work, not others!) of what was going wrong and what was helpful for them. I swallowed my pride and watched as they walked me through their journey of using a report and all the pain points and barriers they encountered.

Let me tell you. It was FASCINATING.

Here are some of the quotes from the interviews:

“Long lists of factual information is not particularly helpful to me. I need something specific and insightful to take action on rather than just generalized themes or watered-down information. For instance, telling me the users were frustrated at the experience frustrates me. What about the experience is frustrating? What can we effectively change? If 8/10 people failed something, do we know why? What can we do to fix it? Overly vague statements (and lots of them), cause me to not want to deal with implementing research. It just takes too much more time and effort.”

“Trust me, I know I don’t know everything about users and that I make assumptions, just like every other human. But, when you don’t trust anything that I say that isn’t “backed by research,” I get frustrated because then you are presenting things I already knew. I’m all for evaluating our hypotheses, especially bigger bets that we really aren’t sure about, but the worst reports reiterate things that were pretty clear in the first place that don’t actually make a difference to what we can do.”

“Sometimes there are big opportunities that aren’t immediately feasible because of tech or business constraints, and we usually know that ahead of time. If you then present your research that’s all about these practically impossible things, it’s frustrating. I’d rather get data about things we can actually do — get a shared understanding from your stakeholders about what’s not possible and what they actually care about in that moment. What’s really relevant to them? What are they trying to enact change on? That’s the stuff we care about. Believe it or not, we want to make positive changes too.”

“Sometimes I wish researchers would run reports by me first. I’ve had projects put in such a harsh light, highlighting everything wrong with the project, that execs just kill the project before we can make improvements. Sure, some of them should be killed, but it’d be nice to get a heads up on such negative findings so I’m ready with a plan.”

“Create a shared understanding at the beginning of the project that aligns the purpose and expected outcomes — the worst thing I’ve received are insights that have nothing to do with my work or what I’m trying to deal with. A lot of discarded research is the result of the product manager thinking the research would cover certain topics, but the researcher does other things. This is not to say you won’t discover things outside the original outline of research questions, but the core questions have to be answered. Not answering the agreed-upon questions, or not even agreeing on any, is a huge waste of time for everyone.”

Because I hadn’t really dove into the nuances of people receiving these reports and having to do stuff with them, I didn’t really understand the ins-and-outs of the different barriers people encountered. Learning this was immensely helpful because it gave me a different perspective to go off when it came to writing my reports. I had tangible evidence and understanding of what wasn’t going as well.

But it wasn’t all bad. Here’s a list of what I found was helpful when it came to research reports:

Being involved with the research and actually hearing the users talk or seeing the problems they are having

Being able to craft and shape the research plan with the UX researcher so there is a sense of alignment and ownership of the project

The research is relevant to the problems the stakeholder is facing and they have autonomy to act on the research

Understanding the business questions that stakeholders are trying to answer so the most appropriate methods/approaches are picked

The research comes at a time where it can still actually influence decisions — stakeholders seem to lose interest in a project that takes over six months to complete (unless previous specified)

The researcher doesn’t let personal bias interfere with the results and they aren’t pushing negative sentiment where it’s not truly there

A focus on presenting actionable insights, not just facts

There is an understanding about the political nature of a company

The report contains outputs that capture customer quotes, ideally some video clips to bring it to life

The researcher partners with other departments, like analytics to bring some numbers and additional context. Seeing the whole picture is key

For once in my research life, it was good to understand what was working with the reports — typically as a user researcher, I focus on the negative and, when that was all I was looking at, I was overwhelmed. I realized that’s what my stakeholders must feel when I list a bunch of things that went wrong with their idea, prototype, or feature. From that moment forward, I decided to also include a slide of what was going well in my research reports.

And while all this information was good, I had to digest it and understand how I could bring it into action. Just like anything (and like stakeholders said), fact was not enough to take action on, it was time to turn the information into something actionable.

Making the Data Actionable

I took all of the interviews and used affinity diagrams to understand the bigger patterns and trends of what I needed to improve moving forward with my research reports. Unfortunately, I didn’t take screenshots with me so I lost all the diagrams, but I do remember (since I still use these principles!) what the overarching trends were.

I found four main themes:

Shared Understanding

Shared understanding and alignment on a project is literally one of the most critical things to set a research project up for success. I know that we’re talking about a report, which is at the end of the research process, but writing an effective report starts from alignment in the beginning.

If you and your stakeholders aren’t aligned with the project’s purpose, goals, and outcome, there is a good chance someone will be disappointed. My worst studies were when I went off and did research without truly understanding what my stakeholders needed from me. In the end, I would present the research, and people would be like, “Okay, cool, but we needed something else.” It was a devasting response.

When you ask your stakeholders what decisions they are trying to make and what information they think they need to make those decisions, creating a shared plan becomes much easier. You can even ask them what type of outcome they expect.

If your stakeholders are having a hard time articulating this type of information, you can give the following fill-in-the-blank:

I need (information needed) to answer (questions they have) by (x timeline) in order to make (the decisions they need to make).

I typically start every research project with a research plan in which I directly align with the stakeholders on the purpose, goals, decisions they are trying to make, and outcomes of the project. Using that direct information, I’m able to shape a study that makes sense based on what stakeholders are trying to understand, and we are all in agreement with what we’re trying to accomplish when speaking to users.

In addition to this research plan, I also like to have regular check-ins with stakeholders to ensure that we are continuing to go in the right direction with research. Now, I don’t always have these, for instance, if it is a straightforward research project that doesn’t need check-ins, but for longer and more complex studies, I like to check in every two weeks or so and update my stakeholders.

Context + Consequence

Just like quite a few stakeholders mentioned in the interviews, a list of facts isn’t particularly actionable. I really struggled with writing insights (check out this article for a very in-depth explanation of writing impactful insights) for a long time because I didn’t really understand what the buzzword actionable meant when it came to insights.

I would often write insights like they were facts without any context or consequence associated with them. This, coupled with not aligning properly with stakeholders’ needs, left me writing things that just weren’t helpful and were, ultimately, ignored.

Here are some “insights” I wrote a while back.

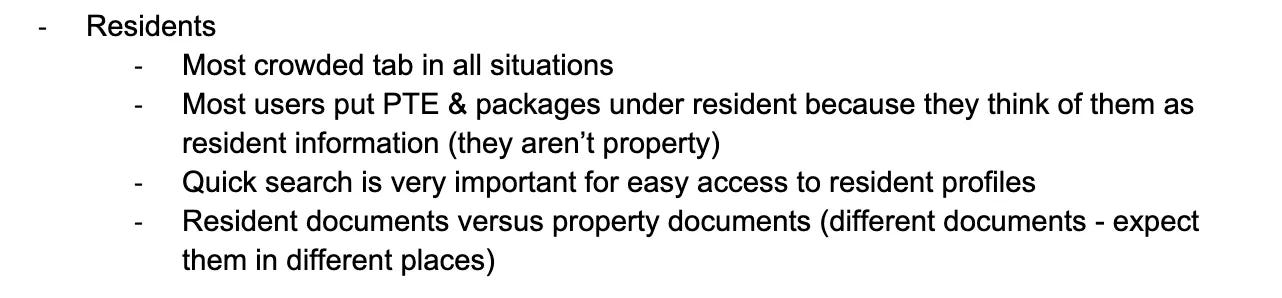

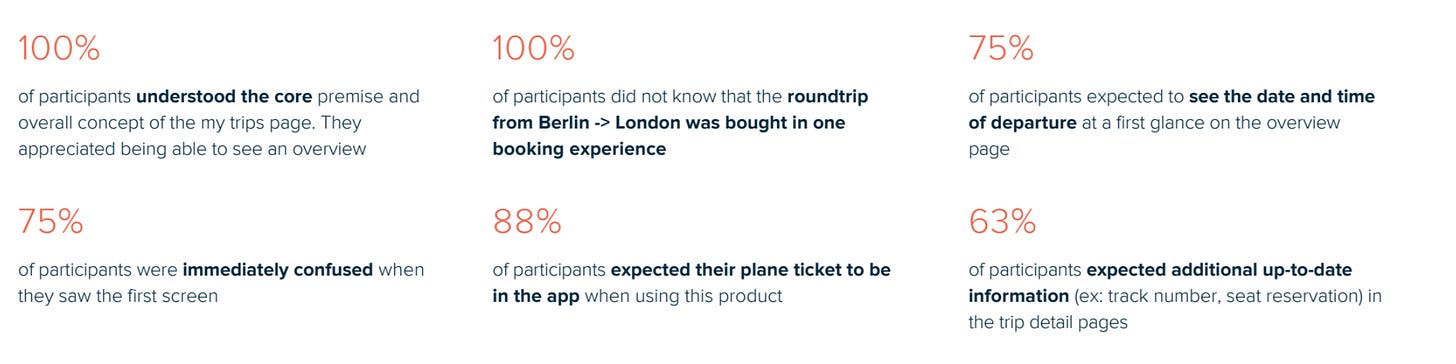

This is the dreaded list of “stuff” disguised as insights or findings. There is absolutely no context or consequence around these different bullet points. In fact, there is really nothing to do because there is not nearly enough information for anyone to take this information and make changes or meaningful decisions.

When I asked for examples of “unactionable” insights, stakeholders shared similar looking lists. Here’s another one of mine they brought up as a prime example:

People were immediately confused when they saw the first screen. Meh. Not great. Cringeeee.

These are good examples of information that lacks context and consequences that could make it actionable.

Again, I now tend to include a “what went well” slide just to reiterate to the team that there are certain things we shouldn’t or don’t have to change. I shied away from this because, when I used to do it, I think I went too overboard, and teams would see all this wonderful stuff and decide that they didn’t really have to make changes because the product was clearly “good enough.”

So, I don’t include positives everywhere, but I do nod toward things that are currently working.

Timing

Time is no one’s best friend, especially in product teams. It always feels like we are running a solid month or more behind on something, and research is no different. Whether it’s because someone came to you too late in the process, recruitment didn’t pan out the way you expected, or literally anything in between, timelines for research can be tight.

And this is made more difficult by ensuring our research is rigorous. We can cut some corners, but not all the corners. So, one thing I learned is to only do research when the timing works out — I now ask my stakeholders how soon they can act on and implement the insights from my work. If it is more than two months, I usually wait to do the research.

Or if I see a research project is going South and we won’t get the research done in time, I try to pivot by either changing the method or putting the research on hold until we can figure something out.

Delivering a report that no one has time to read or act on will usually lead to a lot of disappointment for all people involved. It is disheartening to do all that work and have nothing to show for it. So, as many people say, timing is everything.