Presenting the research no one wants to hear

What to do when your "negative" findings steps on someone’s dream and how to keep your seat at the table

Hi, I’m Nikki. I run Drop In Research, where I help teams stop launching “meh” and start shipping what customers really need. I write about the conversations that change a roadmap, the questions that shake loose real insight, and the moves that get leadership leaning in. Bring me to your team.

Paid subscribers get the power tools: the UXR Tools Bundle with a full year of four top platforms free, plus all my Substack content, and a bangin’ Slack community where you can ask questions 24/7. Subscribe if you want your work to create change people can feel.

You know that sound a meeting makes when the energy drains out of it? The soft click-click of someone scrolling Slack, the PM’s throat clear, the faint shuffle of papers that don’t need to be shuffled.

You just said something important, something that took weeks of work, coordination, and probably a few late nights with messy transcripts, and nobody’s reacting.

You can feel the temperature drop.

That’s the moment every researcher dreads.

You’ve just presented evidence that contradicts what the team wanted to believe. Maybe users didn’t understand the new feature. Maybe adoption is lower than the optimistic model promised. Maybe your usability test showed people getting lost halfway through a flow that was “definitely ready.”

Whatever the reason, your research just stepped on someone’s dream, and you’re the messenger standing in front of the firing squad.

The illusion of “positive” research

Most companies say they love research.

Until it tells them something they don’t like.

Everyone loves a good insight when it validates their roadmap. That’s not research; that’s confirmation theater.

What most teams secretly mean when they say “show us insights” is “show us good news.”

So when you bring something uncomfortable, the energy shifts. You can see the signs:

The head tilt.

The “That’s interesting” in a tone that means “We’re not doing that.”

The immediate pivot to “Well maybe users will behave differently when it’s live.”

That’s the moment where a lot of researchers lose the room—not because they’re wrong, but because they’re unprepared for the emotional weight of truth.

It’s not the data they’re reacting to. It’s the threat.

When your findings contradict someone’s plan, you’re not just challenging the design. You’re threatening someone’s credibility, political capital, and sometimes their bonus.

If you’ve ever watched a PM’s smile tighten after a slide that says “5 of 6 users couldn’t complete checkout,” you’ve seen this firsthand.

They’re not mad at you. They’re scared.

Your data just put their name next to a potential failure.

And when people feel cornered, they fight—just in polite, meeting-friendly ways.

You’ll hear phrases like:

“That’s just early data.”

“We only tested with ten people.”

“We’ll validate that with analytics later.”

It’s self-preservation disguised as feedback.

Understanding that changes how you approach these moments. You’re not fighting against ignorance. You’re navigating power, ego, and loss of control.

Your job isn’t to be liked. It’s to be useful.

When I first started, I thought being right was enough. I’d show up to meetings with a rock-solid report, all the evidence clearly laid out, convinced that logic would win.

It didn’t.

I learned the hard way that truth doesn’t sell itself.

If people feel attacked, they won’t hear a word you say.

What works is reframing your job.

You’re not delivering bad news. You’re mitigating risk.

You’re not saying, “This failed.”

You’re saying, “Here’s what’s blocking the outcome you want.”

It seems like a small shift, but it changes everything.

Instead of “Users hated the dashboard redesign,” say:

“Most users struggled to find the metrics that matter to them. That’s creating friction before value, which is likely reducing adoption.”

Same insight. Different emotional payload.

One sounds like criticism. The other sounds like help.

What’s really happening in the room

When the room turns cold, you’re standing in the middle of three emotional currents:

Self-preservation: Someone’s work, vision, or promotion feels at risk.

Loss of control: People hate uncertainty, and negative data threatens their illusion of control.

Fear of consequence: “If we admit this is broken, we’ll have to change direction. That costs time, money, credibility.”

Once you realize that’s what’s driving their reaction, you can stop taking it personally.

They’re not ignoring you. They’re protecting themselves.

Your goal isn’t to out-argue them. It’s to lower the threat level.

The reframe that keeps you grounded

When you’re facing that silent room, remember this:

Negative results aren’t failures. They’re truths that save money before launch.

They’re the reason you don’t have to explain to the CEO why sign-ups dropped 40% after launch. They’re the reason engineering doesn’t waste a sprint fixing something that never should’ve shipped.

You’re not the problem. You’re the one keeping problems small.

If you can carry that energy into your presentation, you’ll hold your authority without losing your humanity.

Try this mental reset before every “difficult” readout

Before your next meeting, write this sentence at the top of your notes:

“My job isn’t to make people comfortable. My job is to make the product smarter.”

Then ask yourself three questions:

What outcome are they chasing?

What’s blocking that outcome according to the data?

How can I frame this so it feels like progress toward that outcome, not a detour?

Why they don’t want to hear it

Negative results don’t make people angry because of the data. They make people angry because of what the data means. When your findings point to something broken, the people in the room don’t see insights. They see risk; risk to their plans, their competence, their credibility. And unless you understand the flavor of that fear, you’ll waste your energy arguing facts to feelings.

The trick is to stop assuming everyone resists for the same reason. They don’t.

Every stakeholder has their own brand of self-protection, their own internal monologue that starts the second you say, “Users couldn’t find the button.”

The four resistance types

These are the four personalities you meet every time you deliver uncomfortable research. Once you can spot them, you can stop reacting emotionally and start steering the conversation.

1. The Builder: “They just used it wrong.”

You’ll know you’ve met a Builder when they respond to feedback like it’s a personal attack.

You say, “Users struggled to complete checkout.”

They hear, “You’re bad at your job.”

Builders are deeply invested in their craft, often designers or PMs who’ve spent weeks nurturing an idea. Their self-worth is tied to the thing you’re dissecting. When you poke holes in it, it’s like you’re poking holes in them. What to do instead of arguing:

Validate the effort. “You’ve clearly put a lot of thought into this flow, people picked up on the intent right away. The challenge came in step three where they weren’t sure what to do next.”

Shift the focus to alignment. “Let’s look at what’s getting in the way of people seeing that great design work.”

Offer a next step that keeps them in control. “How would you want to tweak this before we test again?”

Once they feel seen, they’ll relax. You’re not trying to prove them wrong, but helping their idea succeed.

2. The Politician: “We can’t show this to leadership.”

These are your optics-driven stakeholders, often department heads or executives who think two steps ahead to what this deck will mean upstairs. Their resistance isn’t about the insight itself. It’s about perception. They’re terrified of looking unprepared, out of control, or like they backed a bad initiative.

You can spot a Politician by the way they redirect. “We don’t need to share that level of detail.” Or, “Let’s frame this as learning, not failure.”

They’re managing spin. Your job is to give them something they can say. How to handle them:

Reframe the finding as foresight. “This gives us an early heads-up before leadership sees it post-launch.”

Use language they can repeat. “We identified an opportunity to improve conversion before rollout.” (They’ll quote that sentence word for word.)

Give them talking points. Literally write out a one-line version of each key takeaway they can use in exec meetings. It makes you an ally instead of a liability.

When you make the Politician look prepared, they’ll protect your credibility in return.

3. The Optimist: “Users just don’t get it yet.”

This one’s easy to spot. The Optimist loves the vision too much to believe it might be flawed. They’ll wave away usability issues with “Once we polish it” or “Once people get used to it.” In their mind, users just need to catch up.

Optimists usually sit in product or leadership roles where their job is to dream big. You don’t want to kill that, you want to tether it to reality without crushing their excitement. How to handle them:

Anchor to their goal. “You want adoption. This friction is what’s standing in the way of that adoption.”

Quantify the cost of waiting. “For every week we hold this issue, we lose X potential conversions.”

Turn it into an experiment. “Let’s prove your hunch. If users ‘get it’ after the polish, we’ll see it immediately in the next round.”

Optimists calm down when you make it safe to test their belief instead of kill it.

4. The Scapegoater: “Those weren’t real users.”

Ah yes, the all-time favorite.

Whenever a result feels uncomfortable, the Scapegoater questions the validity of the research itself. They’ll nitpick methodology, participant count, or recruiting criteria. “Were those our real customers?” “Ten people isn’t statistically significant.” “That’s just one data point.”

They’re not questioning your methods. They’re trying to protect their narrative. How to handle them:

Ground in replication. “That’s a fair question. We can test again with a different segment to see if it holds.”

Call out the pattern, not the number. “We saw six people fail in the same spot independently. That’s the signal we’re surfacing.”

Offer escalation, not defense. “Happy to rerun it if we’re unsure — that’s cheaper than launching and learning it at scale.”

You don’t have to win the argument. You just need to redirect the conversation toward learning. That’s your home turf.

How to use these archetypes

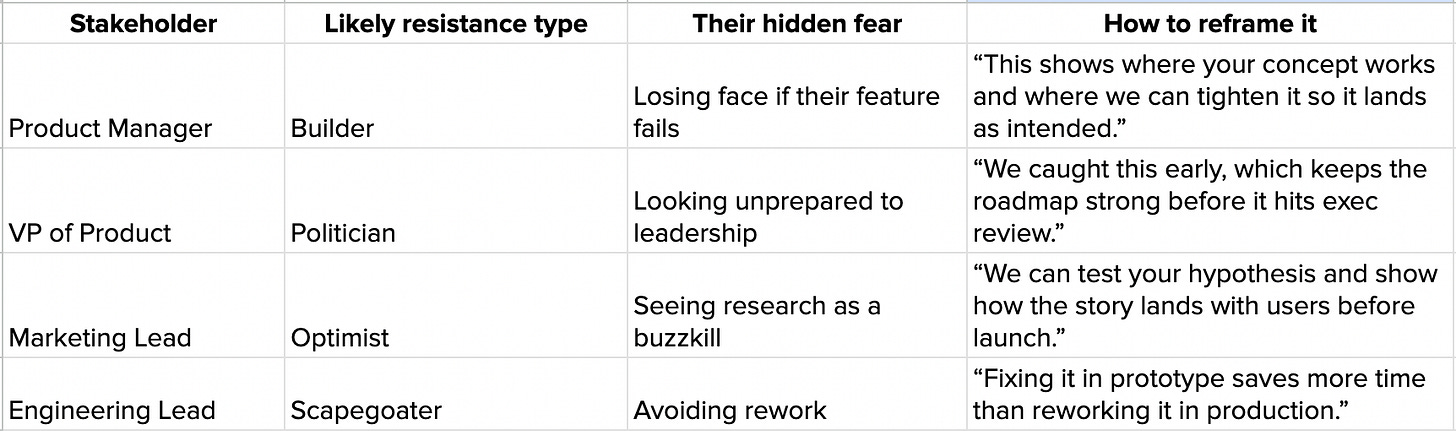

Before your next big readout, sit down and fill out a quick Resistance Map. Grab a piece of paper, draw four columns:

You’ll walk into the meeting already knowing who’s likely to bristle, what they’re afraid of, and what tone will calm them down. You’re preparing for the reality that research is political. The Resistance Map gives you control before the conversation starts.

The mistake most researchers make

They try to bulldoze resistance with proof.

“I have the data.”

“I have the recordings.”

“I have the quotes.”

But data doesn’t change minds. Emotion does. You can’t logic someone out of a defensive reaction. You have to give them a safer narrative to attach to. When you understand what’s really driving their discomfort, you can meet it head-on with empathy and authority at the same time. That’s when your research stops being a debate and starts being a shared decision.

Quick exercise before your next presentation

Pick one upcoming readout. Then, answer these questions in one line each:

Who in the room has the most to lose if this finding is true?

What version of this insight would they feel comfortable repeating to their boss?

How can you say it that way without watering it down?

If you can write those sentences before you walk in, you’ll present truth that lands instead of truth that explodes.

The real pre-work

By the time you walk into a readout, the story has already been written. Not by you, but by everyone’s expectations.